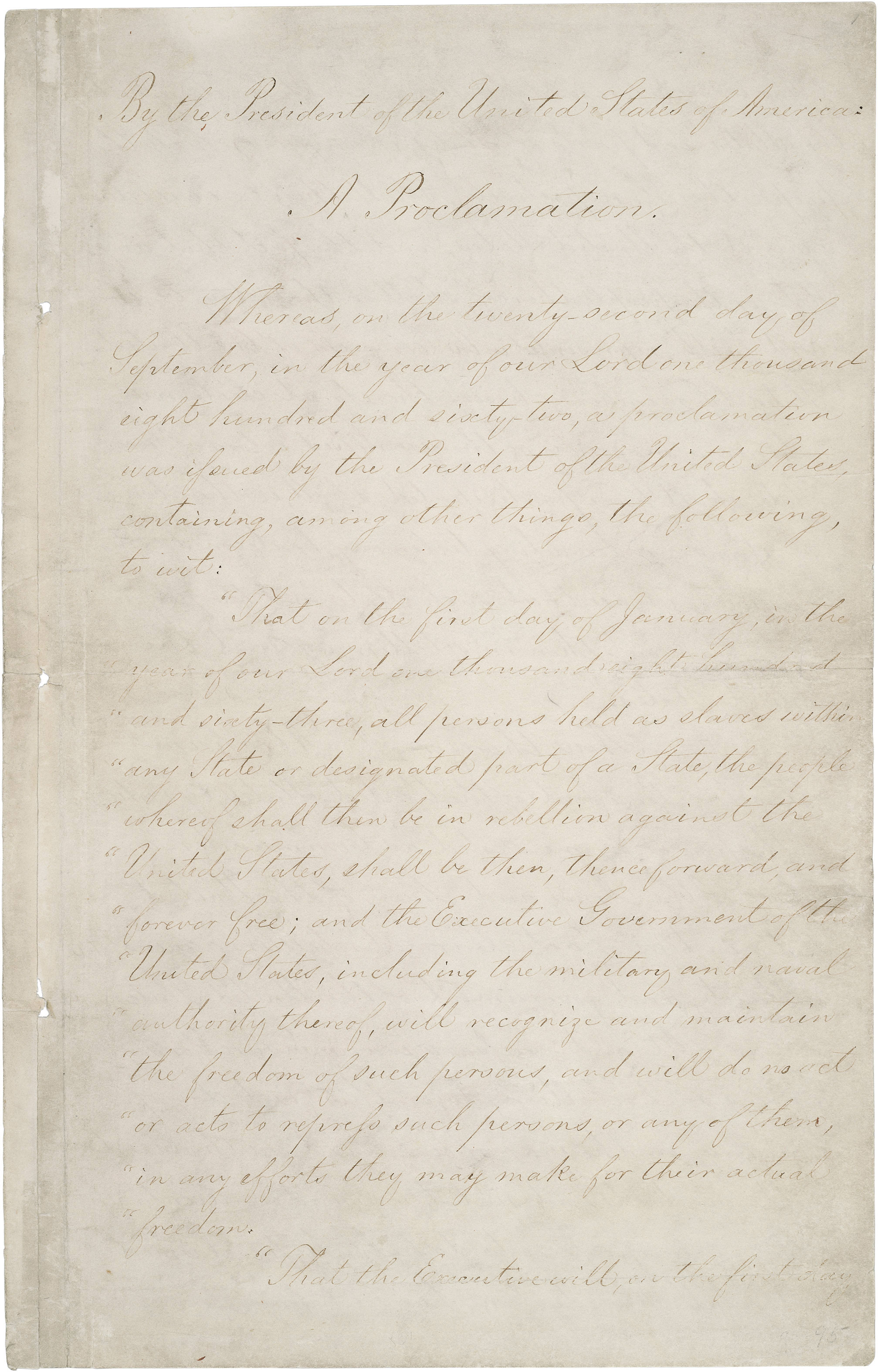

The Proclamation Itself

The Emancipation Proclamation was first read to the Cabinet on July 22, 1862. However, the Secretary of State, William Seward, suggested that Lincoln wait until the Union forces claimed a significant military victory before issuing the proclamation. Due to this compromise, the document was issued on September 22, 1862, after the Union victory at Antietam. Through the Proclamation, Lincoln gave the Confederacy an ultimatum: rejoin the Union or all slaves will be emancipated. By January 1, 1863, the South had not responded, so the Proclamation was put into effect as planned.

The Emancipation Proclamation

The National Archives

The Emancipation Proclamation communicated freedom for all slaves in the Confederate states, unless that state was already under Union control. Thus, the enforcement of the slaves' freedom was dependent on a Union victory in that state. It did not free the slaves in the border states because those states were never "in rebellion against the United States," as the proclamation says. The proclamation also gave the freed slaves the ability to join the Union Army and fight for the North as American soldiers. On the Confederate side, however, the Emancipation Proclamation was understood as a new threat to independence and changed their view on the war: they were now fighting to beome a nation of their own, as well as for the continuation of slavery. But their beliefs worked against them. Their iron grip on slavery undermined their goal of independence: the South was unable to gain support from any European countries, who fiercely opposed the institution, which would almost guarantee their ultimate failure.

The Immediate Results

After the Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863, the slaves in the Confederate states were able to be freed by the Union soldiers who conquered the surrounding Confederate forts. Along with this, the proclamation allowed for freed blacks to join and fight in the Union Army, and over 186,000 African-Americans chose this path. One of the most famous all-black regiments, the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, was crucial in the Union victory at Fort Wagner (shown below). Once the Union won the war, all the slaves were officially free under the 13th Amendment, but they would not be treated as equal citizens for over a century.

Mural of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment at Fort Wagner (2010)

Library of Congress